It was the fate of Captain William Kidd (1645-1701) to be mis-remembered after his dishonourable death and slandered in the centuries since as a common pirate. The legend of his life degenerated to the extent that he was eventually lampooned in the extremely non-classic film ‘Abbott and Costello meet Captain Kidd.’ Another grievous slur against him was that he was actually a native of Greenock – only joking! For those who wish to examine the evidence about his possible west coast origins, please consult the excellent blog Tales of the Oak.

For others interested in his true, Angus origins, read on. Before looking at his life, we can consider how common the family name is in God’s Own County. In the Register of Testaments in the Commissariat of Brechin records for the 17th and 18th centuries there are some 45 people with the surname Kyd or Kidd, most of them around the southern Angus coast and Dundee. Notable members of the family with some sort of maritime connection include John Kyd, Dundee shipmaster (died 1796), the mariner Richard Kyd of Dundee (who died in 1783), and Robert Kyd, ship-master in Montrose (died in 1794). Among the other notable Angus natives who bore the surname was Stewart Kyd, a libertarian, lawyer and native of Arbroath who died in 1811.

In 1841 the surname Kidd (or variants) was the 70th most common surname in Angus. There were shopkeepers in Brechin with the family name (see advert below) and those of a certain vintage who are familiar with the Lochee area of Dundee will well know that Kiddie’s is the popular appellation of the public house officially called the Albert Bar (occasionally frequented by this author in the distant past.). A well known Dundee publisher which flourished in the 19th and 20th centuries was William Kidd. A scout around the graveyards of Angus leads to evidence of the maritime connection; for instance at Broughty Ferry we find the memorial of John Kid, ship-master who died on 15th April 1806, aged 61. The inscription reads:

This life he steer’d by land and sea

With honesty and skill,

And, calmly, suffr’d blast and storm,

Unconscious of ill.

This voyage now unfinish’d, he’s unrigg’d

And laid in dry-dock Urn;

Preparing for the grand fleet trip,

And Commodore’s return

|

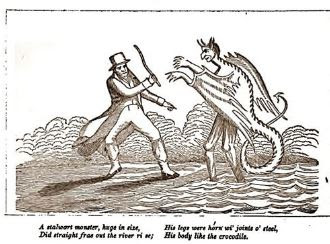

| Does this man have a Dundee face? |

Other branches of the family flourished at Craigie, where Patrick Kyd, married Margaret, daughter of Andrew Wedderburn of Blackness in the 17th century. Patrick’s brother also married a Wedderburn (in fact sister of his brother’s wife). This branch were in possession of Craigie from around 1534 until the middle of the 18th century. Also in 1534 there is a record of Williame Kidd, ‘reidare at Dundie’. Another, later notable man with the same surname is Colonel Robert Kyd (1746-1793), a British army officer from Angus who served in India. Another notable Angus native was Stewart Kyd, d. 1811, a legal writer and politician who was born in Arbroath. Several mercantile Brechiners also had the name and there were several merchants called Kidd in Arbroath in the early 20th century also. Lastly, by by no means least, mention must be made of world wrestling superhero (and latterly publican) George Kidd of Dundee (1925-1998).

There is also a preponderance of the surname Kidd in Fife, just across the River Tay. It has been suggested that the putative link with Greenock was actually derived from an error and the actual place he was linked to was the village named Carnock, near Dundee. What other links are there? Kidd certainly named his cabin boy Dundee, and in a case where he gave evidence in court (Jackson and Jacobs v. Noell in the High Court of the Admiralty), William Kidd stated that he was indeed born in Dundee.

In 1698 it is said that Kidd’s crew forced him into undisguised piracy. They captured a ship named the Quedah Merchant near India. Kidd and his crew captured the ship, which had a cargo estimated at £70000. The Quedah Merchant was renamed the Adventure Prize, and was retained by Kidd. On the journey back to America, Kidd found that he was now a declared pirate and had to tread carefully. Despite precautions, Kidd was arrested, imprisoned and temporarily lost his wits. He was deported to England and questioned by parliament. Despite his previous semi-official work on behalf of the authorities of that country he was convicted, partially through perfidy, and he was hanged on 23 May 1701. His body was displayed in chains on a gibbet for twenty years as a warning to others who chose to follow the occupation of piracy. Since his time there have been various legends about the supposedly buried or sunken treasure which was hidden by captain Kidd before his arrest. Searchers have looked as far apart as Madagascar and North America for his loot, On Grand Manan in the Bay of Fundy, as early as 1875, reference was made to searches on of the island for treasure allegedly buried by Kidd during his time as a privateer. For nearly 200 years, this remote area of the island has been named "Money Cove". In 1983, Cork Graham and Richard Knight went looking for Captain Kidd's buried treasure off the Vietnamese island of Phú Quốc. Knight and Graham were caught, convicted of illegally landing on Vietnamese territory, and assessed each a $10,000 fine. They were imprisoned for 11 months until they paid the fine. But, to date, not one gold piece of Kidd’s supposed hoard has been located.