Bear with me, this is going to be a long one. In the previous piece, I wrote about the places in Angus named Logie and their possible early Christian associations. This post concentrates on the one now in Dundee (historically a parish between Dundee and Liff). More particularly, this is a story connected with

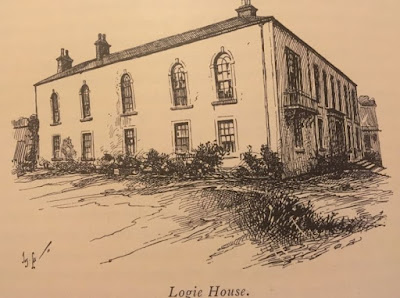

Logie House, a vanished manor house in the area.

The legend of the estate involved another, strange property called

Cradle House and its sad inhabitant, an Indian lady of high birth, though the legend is perhaps not all it seems The fullest account of the house, and also its traditions, comes from chapter 7 of

Lochee, As It Was and Is, written by

Alexander Elliot and published in 1911. I give his full version at the bottom of this article, plus another more literary version contained in

Wilson's Tales of Borders and of Scotland. Out of mercy for any prospective readers I have severely edited the latter, but it's still presented here as a curiosity item and not to be taken as a motherlode of forgotten history!

The History of the House and Estate of Logie

According to the historian Alexander Warden (

Angus or Forfarshire, vol. 4, 18

81 p. 193), part of the lands of Logie passed, at the Reformation, to the Earl of Gowrie and then to Sir David Murray, followed by John Hunter (who also owned the neighbouring estate of Balgay). The other part of the estate of Logie belonged to Dundee. Elliot states that, prior to 1660, one part was still in the hands of this family, being held by David Hunter of Balgay. In that year Hunter sold 'the lands and Manor Place of Logie, near Dundee, together with part of Balgay known as Longforebank' to Sir Alexander Wedderburn, first of Blackness, Town Clerk of Dundee. Logie was sold to Dundee, but bought back by Sir John's son, another Sir Alexander, in 1719.

The history of ownership of the estate (possibly in several parts), with the manor house, was summed up by Alexander Elliot:

Alexander Read of Turfbeg having married Elizabeth Wedderburn, eldest daughter of Sir Alexander Wedderburn, fourth baronet of Blackness, purchased Logie and Longforebank from that gentleman in 1722. Of their sons, of whom they had several, Alexander succeeded to the estate. He married Annie, daughter of Robert Fletcher of Ballinshoe. Indeed, the Wedderburns, the Fletchers, and the Reads appear to have been closely allied by marriage. Sir Alexander Wedderburn of Blackness, who died in 1675, was wedded to Dame Matilda Fletcher; Alexander Read and Elizabeth Wedderburn of Turfbeg were married in 1715; and Alexander Read and Ann Fletcher were united in 1756. The Fletchers have inaccurately been credited with the erection of the mansion.

The house appears to have been built and altered in stages by the Read family between 1722 and 1778. These Reads, or Reids, were related to the Fletchers of Balinscho, and the Reids of Cairnie (near Arbroath). The last of this family was Fletcher Reid, after which the house passed to Isaac Watt, a merchant of Dundee. Then, in 1820, house and some lands went to Major Fyffe (or Fife) of Monikie and a portion of the estate passed to Mrs Anderson of Balgay. From Fyffe the house went to James Watt, then owners named Cleghorn and Black.

The house began to be dismantled in 1905, a process which continued piecemeal for some time. Pior to the First World War, Elliot wrote, 'The rock upon which this interesting edifice stood is undergoing excavation to allow of the extension of Black Street to Lochee Road.'

|

John Wood's Plan of the Town of Dundee, 1821, showing Logie House

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland |

Dark Lady of the Cradle House

The legend of Logie concerns the supposed high-born Indian wife of the owner of Logie estate, who was neglected by her husband in Scotland and left to die of neglect in a strange isolated property on the estate of Logie. This strange house was named

Cradle House, conspicuous because of its odd design, and it was demolished in the early 19th century. The tale also features - as villain - a young man name Fletcher Reid, though Alexander Elliot, in the passage given below, thinks that this man's uncle was the actual antagonist in the story and goes some distance towards investigating the truth.

James Myles (in

Rambles in Forfarshire, 1850, p. 286) gives a short notice of the house and its peculiarities:

In the year 1812, a few yards beyond Logie farm was to be seen a dull, unsheltered, disagreeable looking house of two stories. This house, from having a pavilion formed roof and a short chimney stalk of two flues perched on the top of each of its four corners, was familiarly known as the “Cradle House,” from some fancied resemblance it bore to that useful piece of family furniture, Tradition, not always infallible, says it was built by a former proprietor of Logie for the reception of an East India lady of some rank whom he had seduced, brought here, and then abandoned. There are several stories related about this heartless affair, but all of them are so mixed with the marvellous and incredible as to soar beyond belief.

|

| Logie Street in the mid 20th century, with the wall of Logie Graveyard on the right. |

Foreign Interest in Logie's House of Horror

By the beginning of the 20th century the story of Cradle House had spead far and wide, as exampled by this coverage in the Tuapeka Times, New Zealand, 11th February, 1905:

The Aftermath, The Truth?

Some of the descendants of the 'Black Lady of Logie' are supposed to have lived in Annfield House in Dundee, several miles south of the site of Logie House. This building still survives, stranded in a sea of surrounding tenements. All things considered, the story of the Cradle House and Indian princess of Logie sound extremely flimsy, though there may be some truth buried in the story, somewhere. There is further scope for unearthing the truth, for anyone who has the time and inclination. Tradition seems to state that the Indian princess haunts the area, but this is not certain.

Geoff Holder resurrects the story and admirably summarises the strands of the legend in Haunted Dundee (2012, pp. 83-5), giving the 'facts' a refreshingly sceptical shake up. The Cradle itself he thinks may have been an elaborate summer house, whose ornate Asian architecture possibly went into the melting pot of ingredients which furnished the legend. As for the poor Indian lady herself, she probably did not exist. But he gives us this intriguing thought: 'A post-modern reading may see her as a symbol of the unequal and fractious relationship between Dundee and its flax suppliers in India.' And he adds, pertinently, 'There are absolutely no recorded sightings of the phantom.'

Story Version #1: Lochee - As it Was and Is (1911), Alexander Elliot

The story of the Cradle of Logie and the tragedy with which it is associated has long been a fertile theme upon which the imagination could dwell and the heart go out in sympathy towards the helpless creature who is said to have been the victim. The Cradle House in its time was a weird object in the neighbourhood. It was situated in a hollow some distance west from the gardens, and its foundations were visible long after it became untenanted. Shunned by day, it was regarded with consummate dread after dark. The tale of its erection and the dastardly purpose to which it was put has often been told with a degree of romance, in the circumstances altogether excusable. Taken in the concrete, and making due allowance for the vagaries of a credulous time, the wonder is, if the incidents related were founded upon fact, that no real tangible record of them has been kept. Thomson, adverting to the Cradle, with some caution, says, "it seems to have been erected by a former owner of Logie for the reception of an Indian lady whom he had seduced, brought here, and then abandoned." But he does not penetrate the veil, and gives no clue to the perpetrator of the deed. He suggests that the statements evidently are exaggerated, and declares that "there are several stories related in connection with the affair, but all of them are so mixed with the marvellous and incredible as to stretch beyond belief." It is just the marvellous and the incredible that appeal to the superstitious mind, and from which the most fantastic and unreliable narratives are woven. The popular belief is that Fletcher Read, the proprietor of the mansion of Logie at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was accused of the neglect and ill-treatment of his wife, an Indian lady of high caste, and that because of his exalted social status he was permitted to go unpunished. Having regard to Fletcher Read's professional career, it is averred that he was engaged in military service in India under the East India Company.

In his capacity as an officer of rank, narrators say, he had ample opportunity of mingling amongst and becoming intimate with members of the most dignified and exclusive circles. Here the spell of romance creepeth in. A prince, said to be fabulously wealthy, was blessed with a beautiful daughter. To her, rumour avers, Fletcher Read professed ardent attachment. He wooed and was rewarded, not only with her hand, but, if we are to believe all that has been said and written, with her weight in gold added thereto as luck measure. The marriage, it is presumed, was duly solemnised amid great rejoicing and accompanied by the gorgeous pageantry and splendour of an Indian Court.

As the young lady was a favourite child, the Prince, exhibiting much solicitude for her welfare, presumably gave expression to his sentiments. To allay his fears, which he possibly alleged were groundless, the wily husband declared that he would cherish his newly-made wife as tenderly as if she were a child in a cradle. That is the kernel of the story, and it finishes there as far as India and the lady are concerned. The curtain rises upon a different scene—cold, and bleak, and bare compared to the sumptuous clime of a sunny land. Faithful to his promise, so runneth the story, Fletcher Read brought his wife to his Scottish home. It is not recorded how she was received by his staid relatives. Possibly she was regarded as a rara avis, and, for the time being, treated as such. It is said that her portrait is still in existence, either as a painting of some size or in the shape of a cameo, possibly both. This need not of a truth be gainsaid, as one of the ladies of the Read family had a taste for fine art, and was an adept at the brush and palette. In the long run it seems, if not discarded altogether, the Princess was neglected. A small house, detached and situated some distance from the mansion, had been built for her reception. Pavilion-shaped, the corner of each elevation terminated in a short chimney, and gave it the fancied semblance of a cradle. Despite protests and loving endearments on her part, she was compelled to make the Cradle her home, and live separate from her husband, who by this means appeased his own conscience, and fulfilled the promise he made to the Prince, whilst at the same time he got rid of her importunities. During the lady's sojourn in the Cradle House her personal liberty, to all intents and purposes, was as much curtailed as if she had been a prisoner. It is also stated that an ayah had accompanied her from India as an attendant; and that the Prince, suspecting the integrity of his son-in-law, sent an emissary to Dundee on a mission of espionage.

Taking a lodging in Scouringburn, he kept in touch with the lady while she lived. At her death, so the story runs, the ayah and the emissary disappeared, none knew whither, and probably no one cared. Nor are we vouchsafed the slightest knowledge that the husband had apprised his relative of the demise of his daughter. It is probable, for prudential reasons, he did—not as a matter of duty, we would infer, but rather of policy and self-interest. Over this and a great deal more there is complete obscurity. In all probability the remains of the unfortunate Indian Princess were interred in the neighbouring churchyard of Logie.

At all events, Fletcher Read in due time is accredited with having received intelligence of the death of the Prince, his father-in-law, accompanied by an addendum that, as he was heir to a vast fortune, he should repair to India and claim it. Deceived by specious representations, sanguine and expectant, shall we say, he arrived in due course at his destination. Arrangements were made for his reception, and a cavalcade befitting his rank awaited him. Unsuspectingly he was escorted into the interior—and, once again, dense obscuration sets in. Read, it is averred, was heard of no more. If, however, we are to believe certain narrators, he departed this life in a manner more violent than the poor lady he is said to have so cruelly deceived.

Thus, briefly, according to popular dicta, the fateful story of the hapless Princess is outlined. In so far as it applies to that unfortunate personage there may be, and possibly is, much truth in it; but, on the other hand, there is just the possibility that, through lapse of time and the vagaries of imaginative writers, the details may have been greatly magnified, even distorted. In view, however, of recent inquiry several questions bearing on certain phases of the mystery present themselves. In the first place, are we to take for granted that Fletcher Read in reality was the person indicated in the narrative as having mendaciously deceived the lady? Secondly, was he ever in India? If so, did he ever discharge the duty of an officer in the service of the East India Company ? And, thirdly, if he was not the person described in the narrative, who might that individual be?

In answer to the first query, we have to state that we have been unable to discover evidence to establish in any way the averment that Fletcher Read ever was married to the daughter of an Indian Prince; or, further, that he had been connected with the Cradle House and its unhappy associations. On the contrary, we have abundant proof of his marriage to another lady altogether. Amongst the charters in the Dundee Burgh Court Room there is preserved a deed of annuity drawn up by Thomas Marr, a well-known local lawyer in his day, and dated 4th June 1804, in favour of "Jean Scott, my spouse." The document is signed "Fletcher Read," in clear, legible characters. Could anything be more explicit? It is understood that the lady referred to in the document was a member of an influential family connected with the immediate neighbourhood.

In reply to the second query, it is almost absurd to assert that Fletcher Read ever was in India, and that he was engaged in active service as a soldier. The fact is his military experience never extended beyond a lieutenancy in the Angus Fencibles and Forfar and Kincardine Militia under Colonel Riddoch. In Dundee he was known as a gay, heedless man about town, and a member of convivial and sporting coteries. Nor need it be denied that, along with several boon companions, including two foolish seamen who belonged to Lochee, he took a leading part in an outrage on public decency by enacting the Day of Judgment in Logie Churchyard—an escapade, too, very much misrepresented and inflated—and was guilty of other silly and questionable misdemeanours.

Let us turn to the manner of Fletcher Read's death. It is recorded that it .was a violent one, and was carried out at the behest of his reputed wife's kinsfolk in India. The tale has been accepted as veracious for a century at least, and the act was regarded as one of retributive justice. Now, we will show that the reverse is the case. If there was violence of any kind at his passing it was not of the type represented by the sensational storyteller, but was due rather to the free-and-easy bibulous habits of the time. The following extract from the Scots Magazine, 1807, succinctly sums up the manner of his departure, viz.:—

At Shepperton, Surrey, January 22, Fletcher Read, a gentleman well known in the sporting world. He had spent the previous evening with some convivial friends, and was found dead in his bed on the ensuing morning by his servant, having, it is supposed, died through suffocation.

The foregoing, it is hoped, will dispel some of the aspersions cast upon the character of a man who, whatever his follies, did not deserve to be stigmatised because of the sins and shortcomings of someone else.

Now we come to the third query. If it was not Fletcher Read who ill-treated the daughter of the Indian Prince, who was the person ? An indication is made in the direction of another member of the family altogether, and antedates the so-called Fletcher Read episode by many years. The uncle of Fletcher Read Avas Major Fletcher, who was long in India, and who eventually rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the Company's service. Major Fletcher was brother of Mrs Alexander Read of Logie, and a close intimacy seems to have existed between them. The presumption therefore is that, instead of the nephew—the son of a favourite sister—it was the uncle who should bear the burthen of the odium attached to the Indian lady's ill-treatment and premature death. In the desire for empire it is well known that little respect was paid to the rights and privileges of the natives of India, and it is equally an assured fact that many acts of violence and injustice were perpetrated upon the conquered races. Major Fletcher in all probability shared the prevailing indifference, and held in light esteem any act he might commit, no matter how gross.

If Major Fletcher brought the Indian lady to Logie—which he possibly did before he acquired the estate of Lindertis, near Kirriemuir—he must have done so on the sufferance of his brother-in-law, Alexander Read, and his wife, both of whom occupied Logie long after the Major had disappeared. The inference, therefore, is that the Major had resided at Logie as a member of the family for a time sufficiently lengthy to cover the period of the Cradle incident. If Major Fletcher was the husband of the poor lady—and everything points in the direction that he was—then her death must have taken place previous to 1780. In that year we find him arranging for the disposal of his worldly affairs in favour of John Wedderburn, of London. The deed, according to the "Wedderburn Records," is dated January 13, and is recorded in the Books of Council and Session, 29th Feb. 1780. The Major is described as Thomas Fletcher, Esq. of Lindertis, Lieutenant-Colonel in the service of the East India Merchant Company, and amongst other trustees named is Mrs Ann Hunter alias Fletcher, his spouse. Again, a disposition is confirmed on 9th December 1799 to John Wedderburn of several properties, including Lindertis, by the only surviving trustees of the late Thomas Fletcher. Neither the date of his death nor the manner by which it was encompassed has been ascertained as far as research has gone.

After the death of the Princess, Major Fletcher, it is understood, married Ann Hunter, daughter of the Laird of Blackness, who was one of his trustees. When the Major departed for India it appears that she accompanied him. Such, however, was the hostility of the friends of the deceased Princess, who were in waiting, that it is told she had to be concealed to escape their fury. No satisfactory explanation of the Major's death is vouchsafed. The popular version is that it was one of retribution, suffered at the hands of outraged kinsfolk, whilst a writer states that he was killed in an encounter with the celebrated Hyder Ali, by whom he was cut to pieces. There is just the probability that the manner of Major Fletcher's end having reached the public in a garbled form, had seized upon the popular imagination, and become warped and distorted into the version commonly accepted. Verily the story from beginning to end is a bit of a tangle, unravel it who may.

|

| Hyder Ali Khan (d. 1782), sultan of Mysore, southern India. |

Subsequently, after her return home, Mrs Fletcher became the wife of Mr Thomas Mylne, the proprietor of Mylnefield, near Invergowrie. It is also averred that the Princess left two children, who were taken in charge by their stepmother and educated. In after years, it was rumoured, they went to India, where they attached themselves to their mother's people. After the death of Mr Mylne and the disposal of the estate to another owner, Mrs Mylne resided in the Dowager House at Kingoodie, where she continued to live until a more suitable residence on the Blackness estate was provided for her. This mansion, which is still extant, though its once beautiful grounds are covered with streets and modern tenements, was known as Annfield, the house and adjoining street being named after the lady. Mrs Mylne died in 1852 at the great age of 103 years. Such, therefore, is the story of the "Dark Lady of Logie," presented in a new light, and, it is hoped, divested of some of its weird mystery.

From the foregoing brief narrative the impartial reader will be enabled to discriminate between parties, and doubtless, despite the illusions of romance, apportion the blame to those who ought in fairness to bear it. (note.—For the information relating to the Dark Lady's children and their residence with their stepmother, Mrs Mylne, at Kingoodie, circumstances not hitherto noticed, and other valuable hints, I am indebted to Mr A. Hutcheson, F. S.A.Scot., Broughty Ferry, who has had special opportunities of knowing the case and attendant incidents.—A. E.)

|

| Alexander Hutcheson |

Story Version #2, Vol. 23, Wilson's Tales of the Borders and of Scotland, Alexander Leighton

It was in my very early years that I saw the Cradle, and heard, imperfectly, its tale from my mother; but her account was comparatively meagre. I sought long for details; nor was I by any means successful till I fell in with a man named Aminadab Fairweather, a resident at the Scouring Burn, in Dundee, who was in the habit of frequenting Logie House, and who, though very old, remembered many of the circumstances.

Mr. Fletcher of Lindertes,[*] who was proprietor of the mansion, was the greatest epicurean and glossogaster that ever lived since Leontine times. Then a woman called Jenny McPherson, who had in early life, like "a good Scotch louse," who "aye travels south," found her way from Lochaber to London, where she had got into George's kitchen, and learned something better than to make sour kraut, was the individual who administered to her master's epicureanism, if not gulosity. Nay, it was said she had a hand in the tragedy of the Cradle; but, however that may be, it is certain she was deep in the confidences of Fletcher. But then Mrs. McPherson... delighted in having [friends in Logie House.] It happened that our said Aminadab was one of those favoured individuals; and it is lucky for this generation that he was, for if he had not been, there would assuredly have been no records of the Cradle and the black lady.

[*: Mr. Fletcher had also the property of Balinsloe as well as Logie. They've all passed into other hands.]

It was in a little parlour off the big kitchen that Janet received her henchmen. And was there ever man so happy as our good Aminadab?--and that for several human reasons, whereof the first was certainly the Logie flesh-pots; the second, the stories about the romantic place wherewith she contrived to garnish and spice these savoury mouthfuls... And their happiness would certainly have been complete if it had not been--at least in the case of Aminadab--that it could be enjoyed only by passing through that grim medium, a churchyard... Aminadab could not get to the holy of holies except by passing through Logie kirkyard, a small and most romantic Golgotha, on the left of the road leading to Lochee, whose inhabitants it contained, and which was so limited and crowded, that one might prefigure it as one of those holes or dungeons in Michael Angelo's pictures, belching forth spirits in the shape of inverted tadpoles, the tail uppermost, and yet representing ascending sparks. The wickets that surrounded Logie House--lying as it does upon the south side of Balgay Hill, and flanked on the east by a deep gully, wherethrough runs a small stream, which, so far as I know, has no name--were locked at night. The terrors of this place, at the late hours when these said henchmen behoved to seek their savoury rewards, were the only drawback to Aminadab's supreme bliss.

No churchyard, except those of Judea, was ever invested with such terrors... There was, in that small place of skulls, a rehearsal of the great day [of Resurrection]. We hear little of these freaks now-a-days; but it was different then, when men made themselves demons by drink. One night William Maule of Panmure, then in his days of graceless frolic; Fletcher Read, the nephew of the laird, and subsequently the laird himself, of Logie; Rob Thornton, the merchant, Dudhope, and other kindred spirits... sallied drunk from the inn. The story goes that the night was dark, and there stood at the door a hearse, which had that day conveyed to the "howf," now about to be shut up because of its offence against the nostrils of men who are not destined to need a grave, the wife of an inconsolable husband and the mother of children; and thereupon came from Maule's mouth--for wickedness will seek its playful function in a pun--the proposition that the bacchanals should have a rehearsal in the kirkyard of Logie.

They all mounted the hearse, Panmure being driver... The night was as dark... and the hearse, as it slowly wended its way up the road to Lochee, every now and then pouring forth from its dark inside peals of laughter. The travellers on the road look with wide eyes at the grim apparition, and flee. They arrive at the rough five-bar stile; it is thrown back, and the hearse is driven into the place of the dead...

Now was the time for the trumpet-call, sounded by...Panmure.

"Justice," cried Maule. "Stand out there, Bob Thornton, and answer for the sins done in the body." Thornton stands forth shrieking for the said mercy.

"Was not you, sir, last night, of the time of the past world, in the inn kept by Sandy Morren... drinking and swearing?"

"I was."

"Then down with you to the pit which has no bottom whatsomever."

And Thornton disappears in the hollow not far from where the brick Cradle stands.

"Stand forth, Fletcher Read."

"Weren't you, sir, art and part in confining in yonder dungeon the poor unfortunate black lady, whereby she was murdered by that villain of an uncle of yours, Fletcher of Lindertes?"

"I was."

"Down with you to the pit and the lake of brimstone."

And down he went into the same valley.

"Stand forth, Dudhope."

"Were not you, sir, seen, on the 21st of December of the late dynasty of time, in the company of one of these denizens of Rougedom in the Overgate, that disgrace of the last world, for which it has very properly been burnt up like a scroll of Sandy Riddoch's peculations?"

"I was."

"Then down to the pit."

And so on with the rest, till there were no more to go down... The horn having sounded, there stood forth a figure that did not belong to this crowd of sinners. It was a woman dressed in dark clothes, with a black bonnet, and an umbrella in her hand. How the great God can show his power over the little god, man! The woman was no other than a Mrs. Geddes of Lochee, who, having got a little too much at the Scouring Burn, had, on her way home, slipped into the resting-place of her husband, who had been buried only a week before, and having got drowsy, had fallen asleep on the flat stone which covered him. In a half dreamy state she had seen all this terrible mummery--no mummery to her; for she thought it real... And Maule, now getting terrified through the haze of his drunkenness, cried out, "Who are you?"

"Mrs. Geddes, Johnnie Geddes's wife, o' the village o' Lochee... I hae been a great sinner. I kept company wi' Sandy Simpson when Johnnie was living, and came here to greet owre his grave."

"A woman!" cried Maule; "then to heaven as fast as your wings will carry you."

Hurrying into the hearse, the party were in a few minutes posting to Dundee in solemn silence, where they arrived about two o'clock, not to resume their orgies, but to separate each for his home, with the elements in him of a sense of retribution, not forgotten for many a day.

After hearing the previous tale, Mrs McPherson asks her friend Aminadab if he knows any traditions about the strangely shaped Cradle House. She did indeed and related how her master found a wife in India.

"You know, Aminadab, that my master came from Bombay some years ago, and brought home with him a black wife. Dear, good soul--so kind, so timid, so cheerful too; but, Heaven help me, what could I do?--for you know Mr. Fletcher is a terrible man. He does not fear the face of clay; and the scowl upon his face when he is in his moods is terrible. I am bound to obey."

"But what of her?" said Aminadab. "It's no surely she who is in the horrid hole?"

"Ah well, then, we have it all among the servants how Mr. Fletcher got my lady. He was a great man in Bombay--governor, I think, or something near that--and my lady was the only daughter of the Nawab or Nabob of some kingdom near Bombay--I forget the strange Indian name. She was the very petted child of her father; and when Mr. Fletcher saw her, she was running about the palace like a wild, playful creature... But the mighty Nabob was unwilling to give her to the white-faced lover, even though he was the governor of Bombay, forbye having Balinsloe and Lindertes in Scotland too...Yet, strange enough too, the Nabob had promised the man who should marry his daughter the weight of herself in fine Indian gold, weighed in a balance, as her tocher. The creature was small, and light, and lithe, and could not weigh much."

"My master was keen for the match; but the Nabob was shy of the white face. And here's a curious thing--I got it from my lady herself. She said the Nabob, her papa, as she called him--for, just like us here, they have kindly words and real human feelings--made a bargain with my master, that if he took her away out of India to where the big woman they call the Company lives, he would be kind to her, and 'treat her as he would do a child which is rocked in a cradle.'"

"That bargain they made him sign with blood drawn just right over his heart; and the Nabob signed, too, for the weight of gold and the jewels. Then came the marriage. They had only been a few months married, when Mr. Fletcher's health having failed him,and ... he came home with his wife, and bought this bonnie place.

The new Mrs Fletcher, Kalee, came with her servant named Agita, or Adi, but neither this familiarity nor her husband made her happy. Despite adoring her husband and giving him two young sons, he quickly grew to despise her and imprisoned her in a dungeon under Cradle House. The princess at length died in confinement. She was secretly buried in Logie Kirkyard. But fate caught up with the evil Fletcher when he was called back to India.

"Ay, Aminadab, he was forced to go by the Government; but maybe the Government was only like a thing that is moved by the storm, and cuts in twain, where its own silly power could do nothing. Before he went, he married a beautiful little woman,[*] perhaps the most spirited in the shire, white as Kalee was black, and come, too, of gentle blood. Why did she marry this man? Had she not heard of the fate of Kalee? Had she not seen the Cradle (still standing in the hollow of the hill)? No doubt; but woman will go through worse storms than man's passion to get to the goal of wealth and honour. Then there is a frenzy in woman, Aminadab. She is like the boys, who seek danger for its own sake, and will skim on skates the rim of the black pool that descends from the film of ice down to the bubbling well of death below. Women have an ambition to tame wild men; ay, even wild men have a charm for them, which the tame sons of prudence and industry cannot inspire. So it was: they were married, and he took her to India."

[*: Afterwards, as I have heard, the wife of Milne of Milneford. She lived till nearly a hundred.]

Fletcher - for very far-fetched reasons - ended up in the hands of the relatives of his first, Indian wife and was summarily executed by them. His second, Scottish wife escaped back to her homeland.

The story of Fletcher has died away in Angus; but at one time it was in every mouth, and many a head was shaken as the Sunday loiterers from Dundee and Lochee passed by the Cradle in their walks on Balgay Hill. I have heard that it was demolished as a disgrace to Scotland somewhere about 1810 or 1812. The hollow where the ruins stood is quite visible yet, and the old circumambulating ghost, which, by-the-bye, has unfortunately a white face, is not yet laid.