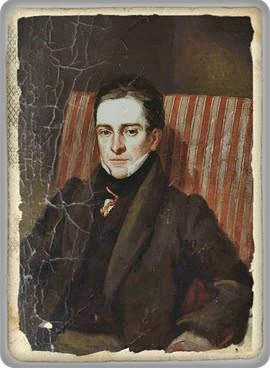

Thomas Hood is not a well remembered figure now, which is a shame because he is one of the more bearable minor English poets of the 19th century. Hood wrote, in relation to the city of his birth, London: 'Next to being a citizen of the world,it must be the best thing to be born a citizen of the world's greatest city.' Despite this, he was from Perthshire stock, in the Carse of Gowrie, and spent part of his short life (1799-1845) in Dundee. Most of the material in this piece is gleaned from Alexander Elliot's Hood in Scotland (Dundee, 1885).

Thomas's uncle Robert Hood became a tutor to the children of Admiral Duncan, later the victor at the Battle of Camperdown and the poet stayed at the house of one of his aunts, Jean Keay, on his first visit to Scotland. The poet's father, another Thomas, was apprentice to a bookseller in Dundee before departing to live in London, where he became a publisher. The poet's father died when he was young and he himself was in his early teens when he was sent back in Scotland for the sake of his health, sailing north on a ship of the Dundee, Perth & London line.

Thomas Hood later took lodgings with a Mrs Butterworth in the Overgate. One of his favourite haunts was the harbour at the River Tay and he got to know the boatmen as he frequently crossed to Newport where his aunt also had a home. During his time in Dundee there was a tragedy with the ferry sinking, as reported by the Dundee Advertiser, 2nd June 1815:

On Sunday forenoon one of the pinnaces plying between Dundee and Newport, in Fife, suddenly sank about half a mile from the latter port, and out of twenty-three or twenty-four persons supposed to have been on board only seven were saved. From some of the people who escaped and others, we have with great pains collected the following details of this very sad disaster :— About a quarter past ten o'clock the pinnace sailed from the Craig Pier, but as the tide was ebbing, and the sand-bank, which now forms an opposing barrier to the passage, was uncovered, it was necessary to make the circuit of its eastern extremity, and for that purpose, the wind blowing strong from the south-east, the boatmen set her along shore till she was opposite the east harbour. Here those cumbrous and unmanageable sails, called lugsails, were hoisted. The main lugsail was first reefed, but after some altercation among the seafaring people on board, the reefs were let out and the whole canvas unfurled. A yawl belonging to Ferry-Port-on-Craig, with one man on board, was fastened by a tow-rope to the stern of the pinnace to be towed across the river. In this manner, and under a heavy press of sail, the pinnace weathered the bank, when, having shipped some water, a fresh altercation ensued about taking in the mainsail. In a few minutes afterwards the person at the helm rose either to clear the yawl's tow-rope from the outrigger of the pinnace's mizzen, or to assist in taking down the mainsail it is uncertain which—and having accidentally put the pinnace too broad from the wind, she instantly filled with water and went down by the stern. At this moment the man in the yawl, with admirable presence of mind, cut the tow-rope which attached her to the pinnace, and not only preserved his own life, but afforded the means of saving the seven persons from the pinnace.The captain of the vessel was John Spalding, known as Ballad Jock or Cossack Jock. Thomas Hood made the incident the subject of one of his early prose pieces. During the summer of 1815, Hood spent some time living with his father's other relatives in Errol in the Carse of Gowrie. Back in Dundee in December he scribbled a long doggerel poem satirising the city to his relatives in London, beginning:

The town is ill-built, and is dirty beside,

For with water it's scantily, badly supplied

By wells, where the servants, in filling their pails.

Stand for hours, spreading scandal, and falsehood, and

tales.

And abounds so in smells that a stranger supposes

The people are very deficient in noses.

Their buildings, as though they 'd been scanty of ground,

Are crammed into corners that cannot be found.

Or as though so ill-built and contrived they had been,

That the town was ashamed they should ever be seen.

The full-scale comical tour of the city which Hood anticipated writing - the Dundee Guide - was never accomplished and he left Scotland soon afterwards.

|

| Hood's first residence in Dundee, the Overgate. |

The poet did not come north again until 1843, accompanied by his son and daughter, again for the sake of his health. he stayed for a while with his aunt Jean and her retired seafaring husband at Tayport, just across the Tay. At his death, two years later, Thomas's sister wrote to her Scottish relatives:

My dear Aunt,—My poor brother is at last released from his sufferings. He departed this life about half past five o'clock on Saturday night. For the last three days he had been insensible. It was only by his groaning occasionally and heavy breathing that we could perceive life in him. I did not expect that he would have lived through Thursday night. When I saw him then he was unconscious, and had not spoken since Wednesday noon, except the words, 'Die, die!' Indeed, I may say, he has been for some time desiring his departure. It has been a lingering death, and his sufferings have been very great; but everything that could be suggested was done to endeavour to alleviate them. Poor Mrs Hood, I am afraid, will feel very much when all the excitement of the funeral is over, for she has been a devoted and attentive wife to him day and night, and had very little rest for some months past and as she said she had no time to write to me, I have been obliged to ride up every week to St. John's Wood, sometimes twice or three times, if I wished to know how he was, when he was in danger. He expressed himself as composed in mind, and prepared for death...With love to you and uncle, I am your affectionate niece,

Eth. Hood.