One of the most fascinating characters of the reign of James VI in Angus was Dr David Kinloch, a native of Dundee. Despite his prominence he receives little attention in standard works on Scottish medicine. He is given one sentence in John Comrie's History of Scottish Medicine (2 vols., 1932) and in David Hamilton's book The Healers, being afforded only the following scant notice:

Another physician who travelled dangerously was Dundee's David Kinloch (1559-1617), M. A. (St Andrews) M. D. (Paris), a writers in obstetrics and a poet. When travelling in Spain he was seized by the Inquisition, but his execution was delayed by the illness of the Inquisitor. Kinloch, the legend goes, sent a message (via a black cat) successfully offering his services and advice, and on the recovery of the Inquisitor, he was allowed to go free.

Kinloch's Background and Upbringing

Kinloch descended from a family in Fife, taking their name from the barony of Kinloch, and his mother was a Ramsay and his maternal grandmother was a Lindsay, related to the Earls of Crawford, who were major landholders in Angus. There are records of medical men named Kinloch (two Williams and a John) in Dundee preceding his time and Dr Buist believed that these were from the same family, but was unsure of the exact relationship between them. Sir Alexander Kinloch of that Ilk succeeded to the barony in the 16th century. There is some uncertainty about the immediate ancestors of Dr Kinloch. His great-grandfather was probably James Kinloch, treasurer of Dundee. One writer states that Sir Alexander's s brother George had several sons, including David, a seaman of Dundee, father of the doctor. The following is from The History of Old Dundee (p. 164):

His family had for some time occupied the position of substantial burgesses. William, [Dr Kinloch's] father, was employed by the Council on an important mission regarding the capture of an English ship in 1563, and he held possession in 1581 of 'the land lying on the north side of the windmill,' as also of 'the meadow lying on the north side of the burial place,' which had been part of the Gray Friars' lands, and continued to be called Kinloch's meadow long after it was acquired by the town.

The writer of the above, Alexander Maxwell, believed that David Kinloch was the doctor's grandfather. Another source states that Dr Kinloch's father was named John. In 1567, there is record of a Thomas Kinloch in Dundee, master of a ship named The Primrose. It is likely the marine link continued in some branch of the family, since there is mention of a ship associated with Dundee named The Good Fortune in 1615. Whoever his father, David Kinloch was born in Dundee in 1559 and he attended St Andrews University in 1576, but he did not graduate.

Foreign Travel

Like many other Scots, Kinloch went to Europe to finish his education. He seems to have studied in Montpellier and there is a reference to the city of Rennes in Brittany in the brieve letter detailed below. Kinloch is said to have made connections with the French royal court.

|

The brieve letter or passport was granted to David Kinloch, on March 20th, 1596, bearing the signature of King James VI. It advises that Dr. Kinloch is going to reside for some years in Rennes and vouches for the fact that he is of noble blood, as is indicated by the coats of arms appended to the passport showing his descent and by a short detailed account of his genealogy. The Kinloch family are described as of moderate knightly rank. The arms show the coats of Kinloch (differenced for a third son), Ramsay, the Earls of Crawford, and the Hay family.

The Inquisition

There does not seem to be any early account of Dr Kinloch's misadventures in Europe. But the following account (from Roll of Eminent Burgesses of Dundee, Dundee, 1887, p. 93), gives a good summary:

During his second voyage it was his misfortune to fall into the hands of the Spanish Inquisition, by whom he was condemned to death as a heretic. The consistent tradition still current in the family relates that his execution was delayed for some time, and that when he inquired as to the cause of his protracted imprisonment, he was informed that it had been intended to make him one of the victims of an auto da fe, but that the illness of the Grand Inquisitor had prevented the accomplishment of this purpose. He then disclosed the fact that he was a practitioner of medicine. and discreetly suggested that it might be within his power to bring about the recovery of this high official. As the case was a desperate one, his suggestion was adopted, and, through the exercise of his skill, he was enabled to restore the patient to health. The grateful dignitary not only set KINLOCH at liberty, but also loaded him with marks of special favour, and procured for him one of the Orders reserved for nobles of the higher rank. The portrait of Dr KINLOCH, which is now at Logie House, shows him in his robes as a physician. bearing the decoration which he had thus gained by his ability.

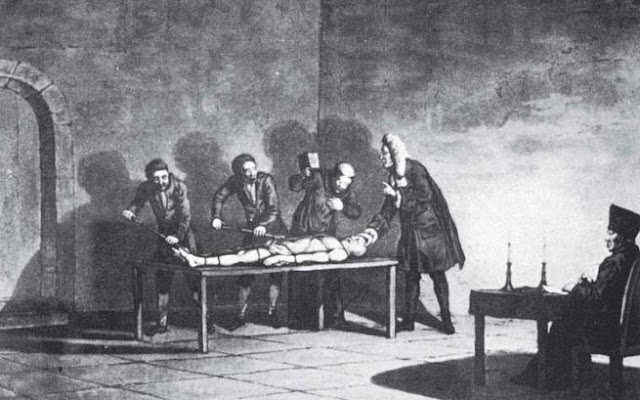

Kinloch seems to have been accused of Lutheran heresy by two Englishmen in Madrid. These men had known him in France, but Kinloch lodged a defence that he was a true Catholic, as was well known in that country. He further claimed that he had only assumed the guise of being a Protestant in France to further his pursuit of a Breton lady named Mademoiselle de Malot. The Inquisition records reveal that the doctor was submitted to torture, but they also give praise about his medical abilities and his pleasant personality.

There is some mystery about what he was doing in Spain and he certainly must have been aware of the potential danger he was facing before he entered that country. It is possible that Kinloch was on a mission for King James VI. The king had appointed him Mediciner in 1597 and there is the suggestion that he had conducted missions abroad for the monarch. Was he is Spain to sound out the possibility of securing a marriage alliance with the Infanta and James's son Prince Charles? It is unlikely that we will ever know for certain.

Dr Kinloch evidently brought home from Spain a set of Inquisition thumbscrews which were kept as an heirloom by successive generations of the Kinloch family. (They were lent to an exhibition in Glasgow by descendant Major-General Kinloch. See Palace of History, Catalogue of Exhibits, vol. 2 (Glasgow, 1911), p. 949.)

Further details about the ordeal of Dr Kinloch were uncovered in Spanish archives in 1998 by Laura Adam and Adam Yagui-Beltran and an account of the findings published in The Innes Review. Although Kinloch passed details of his abysmal treatment in Spain to his family and the true legend was passed down the generations, he left no full account of the depth of suffering which he endured there. Some measure of his suffering can perhaps be gleaned by having reference to his fellow Scot, William Lithgow, who was arrested in Malaga several decades after. He was nearly tortured to death by the Inquisition and was only saved by the ministrations of two slaves. Sentenced to death for being a heretic Calvanist, he was only saved by the intercession of the town's governor. He went back to Scotland, having lost the use of his left arm, and wrote a full account of his time under the Inquisition and journeys, The Totall Discourse of the Rare Adventures and Painefull Peregrinations of Long Nineteene Years Travayles (1632).

Legend of the Black Cat

While in prison, Dr Kinloch heard that the Grand Inquisitor had fallen ill and he resolved to pass a message to him by means of writing a message to the authorities, offering his medical services, and attaching it to the prison cat. This tale too may have been passed down through the Kinloch generations. It has all the hallmarks of a folk tale, but I can find no very early version of the story. Her is a summary given by K. G. Lowe:

his life was only spared by his curing the Grand Inquisitor who had lain 'dying of a strange fever'. Apparently Kinloch hearing of the strange illness tied a message to the tail of a black cat with which he shared his daily ration and sent it through the bars of his cell, fortunately reaching the right quarter.

The Later Years: Honours, Plague, Trouble with the Law

Kinloch became a burgess of Dundee on 17th February, 1602, and settled in the burgh. Kinloch's wife Grissel was daughter of Hay of Gourdie and related to the Hays of Errol. They marries several years earlier, following Kinloch's return from Europe. The couple had two sons and a daughter. Their house stood on the west side of Couttie's Wynd, near the present Union Street in Dundee. (The house was apparently leased to a another physician, William Ferguson, when the doctor was abroad. His first wife, Eupham, was Dr Kinloch's sister.)

A great 'pest' attacked the city of Dundee in 1607, which is likely to have been typhus rather than bubonic plague, though its effects were just as deadly. A great many inhabitants were carried away and Dr Kinloch's services would have been greatly in demand. Among those he attempted to save was the brother of eminent Dundonian Peter Goldman, who wrote a vivid description on the disease ravaged burgh.

Dr Kinloch's land holding is described in Council Minutes: 'his foreland lay foreanent the wind mill' at Yeaman Shore. In 1610 the council took action against the family because of an alleged encroachment upon the public road. According to Alexander Maxwell:

However, the row escalated to the Privy Council. Kinloch complained in 16th August that the Dundee baillies William Ferguson and Walter Rollok had cast down a 'prettie piller of stone werk' which he had erected on his own land 'for setting thairon of his banefire'. It is perhaps a measure of Kinloch's standing that the town authorities could not reproach him directly regarding his unauthorised building work but had to target his hapless builders. It's possible there may have been some earlier complications with Kinloch trying to remove Dr Ferguson from his house.

A measure of Kinloch's kindliness is perhaps preserved in another record from the Privy Council, where he was indirectly involved in another incident in the year 1613. A man named James Baldovie complained that his ward had been abducted by a suitor called John Ramsay. But Margaret gave evidence of his own assent in the matter, stating that it was 'hir awne propir will and motive' that she left James and went directly to Dr Kinloch in Dundee, whom she described as her friend. She stated firmly that she intended to marry John and the Privy Council found in her favour. I would guess perhaps that the young lady was a relative of Dr Kinloch's family on his mother's side.

A great 'pest' attacked the city of Dundee in 1607, which is likely to have been typhus rather than bubonic plague, though its effects were just as deadly. A great many inhabitants were carried away and Dr Kinloch's services would have been greatly in demand. Among those he attempted to save was the brother of eminent Dundonian Peter Goldman, who wrote a vivid description on the disease ravaged burgh.

Dr Kinloch's land holding is described in Council Minutes: 'his foreland lay foreanent the wind mill' at Yeaman Shore. In 1610 the council took action against the family because of an alleged encroachment upon the public road. According to Alexander Maxwell:

He had already made an encroachment upon another man's right, by striking furth a window in a mutual gable without obtaining his leave, but was obliged to become bound 'to condemn and to close up the licht at sic time as it should please' his neighbour to raise his house higher. [The History of Old Dundee, p. 163.]The couple apparently then engaged tradesmen to engage on surreptitious building work: 'under silence of nicht, to big ane pillar [or wall] of stone wark upon the common street and bounds thereof, betwix his tenement and the windmill'. At a meeting of the burgh council on 17th July, 1610, three masons stated, 'that before sunrising at the command of Griseld Hay, the spouse of Dr David,' they illegally built a pillar of stone work adjacent to the common road. They were fined £5 and ordered to:

demolish the said pillar to the ground and restore the common gait on passage to the auld estate.

However, the row escalated to the Privy Council. Kinloch complained in 16th August that the Dundee baillies William Ferguson and Walter Rollok had cast down a 'prettie piller of stone werk' which he had erected on his own land 'for setting thairon of his banefire'. It is perhaps a measure of Kinloch's standing that the town authorities could not reproach him directly regarding his unauthorised building work but had to target his hapless builders. It's possible there may have been some earlier complications with Kinloch trying to remove Dr Ferguson from his house.

A measure of Kinloch's kindliness is perhaps preserved in another record from the Privy Council, where he was indirectly involved in another incident in the year 1613. A man named James Baldovie complained that his ward had been abducted by a suitor called John Ramsay. But Margaret gave evidence of his own assent in the matter, stating that it was 'hir awne propir will and motive' that she left James and went directly to Dr Kinloch in Dundee, whom she described as her friend. She stated firmly that she intended to marry John and the Privy Council found in her favour. I would guess perhaps that the young lady was a relative of Dr Kinloch's family on his mother's side.

David Kinloch purchased the lands of Aberbothrie Bardmony and Leitfie in Perthshire from Patrick Lord Gray, which were confirmed by a charter of James VI in 1616. He also purchased the estate of Balmyle and changed its name to Kinloch. This became the main residence of the family for several centuries.The original house, near Meigle in Strathmore, was destroyed by fire. A replacement mansion was built in 1797, but passed from the hands of the Kinloch family. The building was latterly turned into a hotel.

Death and Memorial in The Howff

It is likely that death came fairly suddenly to Kinloch and not after a long illness, for two months before his death on 10th September, 1617, he received permission to venture abroad. He was laid to rest with great ceremony in Dundee's main burial ground, the Howff. The monument still exists, near the north-west gate, though the inscription was erased later. The inscription to Dr Kinloch eulogised him, in Latin, as 'a most honourable man, of famous learning, and in his life adorned with many singular virtues; a most skilful physician to the Kings of Great Britain and France, by whose patents and seals the antiquity of his Pedigree and Extract is clearly witnessed and proven...'

Kinnalochi proavos et aviate stemmata gentisClara interproceros haec monumenta probantMagnus ab his cui surgit sed major ab arteMajor ab ingenio gloria parta venit

Gallant Kinloch, his famous ancient race

Appear by this erected in this place;

His honour great indeed; his art and skill

And famous name both side o' the pole do fill.

The inscription was later removed and replaced by an inscription dedication to his descendant, Sir James Kinloch Nevay.

Kinloch the Poet

For many years, Kinloch's fame was supplemented by his reputation for great learning. Dr Kinloch's two long poems on medical subjects De Hominis Procreatione and De Anatome are actually part of a longer whole, published in Paris in 1596, and reprinted in second volume of the Scottish Latin compilation Delitiae Poetarum Scotorum (Amsterdam, 1637). The poems particularly detail the development, anatomy and diseases of man. The book contains poems by his fellow Dundonians Peter Goldman and Hercules Rollock.

Kinloch's Portrait

Dr Kinloch's Descendants

Dr Kinloch and his wife had two sons and a daughter. James inherited the main estate and John gained the estate of Gourdie, near Dundee. James's son, another David, was knighted by King James VII. The family maintained their association with Dundee, though the main branch had its base in eastern Perthshire. The doctor's great grandson, Sir James Kinloch, married Elizabeth, sole daughter if John Nevay of Nevay in Angus. This couple had twelve children. Doctor David's great-great-grandson was Sir James Kinloch Nevay who held Dundee for the Young Pretender during the Jacobite Rebellion, from 7th September, 1745, until 14th January, 1746. A direct descendant was George Kinloch of Kinloch (1775-1833), a reformer and politician. A businessman with interests in Carnoustie and Dundee, he was elected Member of Parliament for Dundee a short time before his death. A statue of him was erected in Albert Square in Dundee in the 1870s and remains there, possibly on the ground which his ancestors had owned, known as Kinloch's Meadow.

Further details of the later family can be consulted in Warden's Angus, or Forfarshire, volume 4, pp. 341-5.

Further details of the later family can be consulted in Warden's Angus, or Forfarshire, volume 4, pp. 341-5.

Selected Sources

R. C. Buist, 'Dr David Kinloch (Kynalochus), 1559 - 1617,' The British Medical Journal, Vol. 1, no. 3409 (May 1, 1926), p. 793.

R. C. Buist, 'Dundee Doctors in the Sixteenth Century,' Edinburgh Medical Journal (June, 1930), pp. 293-302, 357-366.

David Hamilton, The Healers, A History of Medicine in Scotland (Edinburgh, 1981).

David Hamilton, The Healers, A History of Medicine in Scotland (Edinburgh, 1981).

Dr. J. Kinnear, 'Early Dundee Doctors,' Edinburgh Medical Journal (April 1953), pp. 169-83.

K. G. Lowe, 'Dr David Kinloch: Mediciner to His Majestie, James VI,' Scottish Medical Journal (1991), pp. 87-89.

Alexander Maxwell, The History of Old Dundee (Edinburgh and Dundee, 1884).

Norman Moore, 'The Schola Salernitana: its history and the date of its introduction into the British Isles,' (Glasgow, 1908).

Our Meigle Book (Dundee, 1932).

Alexander Maxwell, The History of Old Dundee (Edinburgh and Dundee, 1884).

Norman Moore, 'The Schola Salernitana: its history and the date of its introduction into the British Isles,' (Glasgow, 1908).

Our Meigle Book (Dundee, 1932).

James Paton (ed.), Scottish Life and History (Glasgow, 1902).

Tayside Medical History Museum Art Collection - The Kinloch Portrait

Alexander Warden, Angus, or Forfarshire (vol. 4, Dundee, 1884).

No comments:

Post a Comment