This is the second of three articles which considers the early history and legends of Invergowrie. The first looked at the Roman fort of Catermilley (and can be found here), while the third considers the legends of the Goors or Yowes o Gowrie in relation to the deeper significance of the area as a whole.

The history of St Peter's Church - the Dargie Kirk - is intimately associated with the subject of a future post, the Goors (or Gows or Ewes) of Gowrie, stones were were reputedly thrown by the Devil from Fife as he was enraged at the foundation of the first Christian church north of the River Tay.

The current ruined church is described by MacGibbon and Ross in The Ecclesiastic Architecture of Scotland:

The standard 'facts' about the building were summarised by county historian Alexander Warden in the 1880s:

The place-name Invergowrie, relating to the settlement there, possibly only gained currency in fairly recent times. There were several farm hamlets in the area before the 19th century, one of them called Dergie or Dargie. Another was named Balbunnoch (or Balbunno), 'the reputed site of a battle in ancient times' (Hutcheson, Old Stories in Stones, p. 6). The building of a paper mill and the coming of the railway in the 19th century coalesced the settlements around Mylefield Feus into one village. The Burne of Innergowrie was from an early time (1565) the recognised boundary of Perth and Forfar and probably this was the case for many centuries before. Despite this, there was further confusion because the ancient kirk lay on the left bank of the burn (in Gowrie/Perthshire) while almost the entirety of the lands of Invergowrie lay on the right bank, the Angus side.

Ecclesiastical history has busily blurred the boundaries here (though we won't worry about modern civil parish changes here). Between 1574 and 1613 the parishes of Logie (Angus) and Invergowrie (Perthshire) were merged simultaneously with that of Liff (Angus). The combined territory was then included in Angus. In 1758 this combined parish (named Liff) again grew when it combined with Benvie (Angus) and became known as Liff and Benvie.

What is important to recognise is that the Angus/Gowrie border here possibly preserves the demarcation between ancient Pictish regions here. Borders had a deep symbolic significance. Monasteries were sometimes placed near borders to prevents conflicts in Early Medieval times (an example is Kingarth of Bute, close to the border of Strathclyde and Dal Riada), but also so clerics could have access to powerful groups from both areas. This may be the case here.

In the charter of Malcolm IV dated 1162 x 1164 which gave the place to the Abbey of Scone it is called Inuergouerin. This document states, 'This charter is a gift to God, to the church of the Holy Trinity of Scone, and to the abbot and canons serving God there of the church of Inuergoueren, cum dimidia carucata terre que jacet in occidentali parte ecclesie prenominate nomine Dargoch et cum omnibus pertinentiis ad eandem ecclesiam vel terram pertinentibus in liberam elimosinam, 'with the half ploughgate of land which lies in the west part of the church named Dargoch, together with everything pertaining to the said church or land in free gift.'

Dargoch is the Dergie or Dargie of later times. It is also spelled Dargon and Dargo in documents.

Many sources take the root of Gowrie, as applied to the burn and the whole district, to derive from the native term for 'goat'. Dalgetty states that the local name for the low land between Invergowrie and Longforgan is the Howe of the Goat. The Celtic scholar W. J. Watson. on the other hand, derived the province name from Gabran, ruler of Dal Riada and father of the 6th century potentate Aedan. The area of course was the whole territory immediately west of Angus, not just the coastal plain north of the Tay known as the Carse of Gowrie.

The stone known as the Bullion Stone found just north of Invergowrie in 1934 is a unique artefact (now in the National Museums of Scotland). I wrote about in previously in a previous post very briefly and none too seriously (it can be found here: A Word About the Wee Man). But it deserves more consideration. This sculpture shows a human figure on horseback, but not a young warrior in his prime. Rather he is bearded and balding and none too slender. His mount, going uphill, seems to struggle with its burden. The rider holds aloft a drinking horn whose terminal - a bird's head - stares back at him quizzically. The carving is unique. It has been considered as possibly part of a frieze and this brings to mind the arched stone from the Pictish power centre at Forteviot in Perthshire (also now in Edinburgh) and makes me wonder whether the Bullion Stone, like this one, came from the entrance display of a high status hall or residence here. If so, it has not been discovered by archaeology and may well have been obliterated by widening of the main Dundee-Perth road. But it adds another dimension to the Pictish landscape locally. The visual artist David Watson Hood has a very interesting article about the stone on his website (www.twocrows.co.uk).

Clancy, T. O., 'Philosopher-King: Nechtan mac Der-Ilei,' The Scottish Historical Review LXXXIII; 2, No 216 (2004), pp. 125-149.

Dalgetty, A. B., The Church and Parish of Liff (Dundee,1940).

Grigg, J., The Philosopher King and the Pictish Nation (Dublin, 2015).

Hutcheson, Alexander, Old Stories in Stones and Other Papers (Dundee, 1927).

Jervise, A., 'Notices descriptive of the localities of certain Sculptured Stone Monuments in Forfarshire, viz., - Benvie, and Invergowrie; Strathmartin, and Balutheran; Monifieth; Cross of Camus, and Arbirlot,' Part III. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 2 (3). Vol 2(3) (1855), pp. 442-450.

MacDonald, A., Curadán, Boniface and the Early Church of Rosemarkie (Rosemarkie, 1992).

Macdonald, A. D. S. and Laing, L. R., 'Early Ecclesiastical Sites in Scotland: a Field

Survey, Part II,' Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 102 (1970), pp. 129-45.

MacGibbon and Ross, D and T., The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Scotland From the Earliest Christian Times to the Seventeenth Century, volume 3 (Edinburgh,1896-7).

Macquarrie, A., (ed.), Legends of the Scottish Saints, Readings, Hymns and Prayers for the Commemoration of Scottish Saints in the Aberdeen Breviary (Dublin, 2015).

Philip, Rev. A., The Parish of Longforgan (Edinburgh, 1895).

Scott, The Pictish Nation, its People and its Church (Edinburgh and London, 1918).

Simpson, W. Douglas, 'The Early Romanesque Tower at Restenneth Priory, Angus,' The Antiquaries Journal, 42 (02) (1963), pp. 269-83.

Stuart, J., Sculptured Stones of Scotland, vol. 1 (Aberdeen, 1856).

Taylor, D. B., 'Long Cist Burials at Kingoodie, Longforgan, Perthshire,' Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 93 (1959-60), pp. 202-16.

Warden, Alexander, Angus or Forfarshire, 4 volumes (Dundee, 1880-1885).

Dargie Kirk, Satan and the Picts

The history of St Peter's Church - the Dargie Kirk - is intimately associated with the subject of a future post, the Goors (or Gows or Ewes) of Gowrie, stones were were reputedly thrown by the Devil from Fife as he was enraged at the foundation of the first Christian church north of the River Tay.

The current ruined church is described by MacGibbon and Ross in The Ecclesiastic Architecture of Scotland:

Between 1153 and 1165 the Church of St. Peter, Invergowrie, was given to Scone by Malcolm IV; but of this early structure nothing whatever remains, and the existing building is probably not earlier than the first half of the sixteenth century. The walls of the structure are entire, although the west gable hangs in a very tottering manner. The building measures inside about 46 feet in length by 15 feet 9 inches in width. There are two doorways in the south wall, the one towards the west end being round-arched, but not built on the arch principle, being cut out of two large stones. The other doorway is lintelled. There are two windows also in the south wall, the one being round-arched and cusped and having the arch cut out of a single stone. The other window is lintelled and had a central mullion.The plain rectangular building may date from the 16th century and could possibly be the third church on the site. Some sources state that the building was in decay by the 17th century and probably out of use by the 18th, though the burial ground continued to be used. Internally it was divided into two parts latterly. The eastern half was used for internments by the proprietors of Invergowrie House and the western half was used for the same purpose by the owners of Mylefield Estate. The building is on a slight mound - a characteristic of early church sites - and was close to the shore, though land reclamation means it is now some distance from the water. The only interesting internal feature noted by the authors above was the following: 'Lying inside the church there is the curious cross-like object. It is pierced in the centre, and appears to have had a shaft, which is broken, as shown.'

The standard 'facts' about the building were summarised by county historian Alexander Warden in the 1880s:

The Church of Invergowrie is said to have been erected of wood by Boniface, a papal missionary who introduced the ritual of the Latin or Western Church into Angus, Archbishop Spottiswood says in A.D. 697, but Mills, in his History of the Popes, says in A.D. 431, being the 8th year of the pontificate of Pope Celestine. It was the first Christian church north of the Tay. Boniface built another church at Tealing, and a third at Resteneth. The church of Invergoueryn was dedicated to S. Peter, Apostle, and, with its emoluments, was given by Malcolm IV. (1153-1165) to the Abbey of Scone, of which he was the founder. The canons served the cure by a vicar pensioner, appointed by the Chapter. The church is believed to have been in the diocese and commissariat of St Andrews. It was erected on a small mound near to where the burn of Gowrie, the Plumen Gobriat in Pictavia falls into the Tay. The ruins of the church are roofless and covered with ivy. The parish was small and the area of the church correspondingly limited, but at some period it had been enlarged by the erection of an aisle on its north side. With this addition it had been sufficient for the congregation, as the parish was small. The age of the church is unknown, but it is very old. (Angus or Forfarshire, vol. 4, p. 172.)

Macdonald and Laing describe the setting succinctly:

on top of low natural knoll, with burn running close by to N. Ground configuration suggests occupation build-up under church. Knoll enclosed at base by wall to form roughly oval graveyard. This possibly the outline of [early Christian] enclosure, though no [early Christian] structural remains seen...

Gowrie and Angus - The Borderlands

Invergowrie stands on the border of Angus and Perthshire; more specifically it straddles the demarcation line between Angus and Gowrie, the eastern area of Perthshire. (This is, curiously, also the case with Coupar-Angus to the north.) Nothing being simple, of course, the exact line has fluctuated over the centuries due to amalgamations of parishes etc. As this border is an important issue - to be examined below.

The place-name Invergowrie, relating to the settlement there, possibly only gained currency in fairly recent times. There were several farm hamlets in the area before the 19th century, one of them called Dergie or Dargie. Another was named Balbunnoch (or Balbunno), 'the reputed site of a battle in ancient times' (Hutcheson, Old Stories in Stones, p. 6). The building of a paper mill and the coming of the railway in the 19th century coalesced the settlements around Mylefield Feus into one village. The Burne of Innergowrie was from an early time (1565) the recognised boundary of Perth and Forfar and probably this was the case for many centuries before. Despite this, there was further confusion because the ancient kirk lay on the left bank of the burn (in Gowrie/Perthshire) while almost the entirety of the lands of Invergowrie lay on the right bank, the Angus side.

Ecclesiastical history has busily blurred the boundaries here (though we won't worry about modern civil parish changes here). Between 1574 and 1613 the parishes of Logie (Angus) and Invergowrie (Perthshire) were merged simultaneously with that of Liff (Angus). The combined territory was then included in Angus. In 1758 this combined parish (named Liff) again grew when it combined with Benvie (Angus) and became known as Liff and Benvie.

What is important to recognise is that the Angus/Gowrie border here possibly preserves the demarcation between ancient Pictish regions here. Borders had a deep symbolic significance. Monasteries were sometimes placed near borders to prevents conflicts in Early Medieval times (an example is Kingarth of Bute, close to the border of Strathclyde and Dal Riada), but also so clerics could have access to powerful groups from both areas. This may be the case here.

|

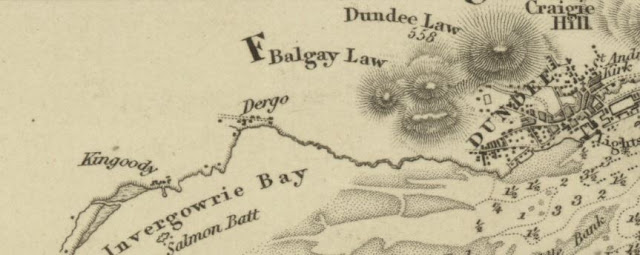

| Admiralty map of east coast of Scotland by George Thomas, 1815. Reproduced with the permission of the National Museum of Scotland. |

In the charter of Malcolm IV dated 1162 x 1164 which gave the place to the Abbey of Scone it is called Inuergouerin. This document states, 'This charter is a gift to God, to the church of the Holy Trinity of Scone, and to the abbot and canons serving God there of the church of Inuergoueren, cum dimidia carucata terre que jacet in occidentali parte ecclesie prenominate nomine Dargoch et cum omnibus pertinentiis ad eandem ecclesiam vel terram pertinentibus in liberam elimosinam, 'with the half ploughgate of land which lies in the west part of the church named Dargoch, together with everything pertaining to the said church or land in free gift.'

Dargoch is the Dergie or Dargie of later times. It is also spelled Dargon and Dargo in documents.

Many sources take the root of Gowrie, as applied to the burn and the whole district, to derive from the native term for 'goat'. Dalgetty states that the local name for the low land between Invergowrie and Longforgan is the Howe of the Goat. The Celtic scholar W. J. Watson. on the other hand, derived the province name from Gabran, ruler of Dal Riada and father of the 6th century potentate Aedan. The area of course was the whole territory immediately west of Angus, not just the coastal plain north of the Tay known as the Carse of Gowrie.

Saint With Two Names? Curetán and Boniface. St Peter and King Nechtan

A recent writer on the confused history of the saint sometimes called Boniface and at other times named Curetán warned from the outset of his work that he was not going to provide definitive answers about whether the two were one saint, or separate intertwined clerics. And neither can I hope to. There is a record of a bishop named Curetán who appears in a list ratifying Adomnán of Iona's Law of Innocents in 697 AD, protecting the rights of non combatants in Ireland and North Britain. St Curetán appears in Irish calendars at 16th March. Other sources for this shadowy figure appear almost deliberately convoluted and contrary. In the Acta Sanctorum there is a certain preacher to the Picts ascribed to the 7th century termed 'Albanus Kirtinus, surnamed Boniface, by nationality an Israelite'.

This man - otherwise called Boniface Queritinius - travelled from Italy in the company of wise men and sailed into the Firth of Tay, 'to the mouth of the little river, which now separated the district of Gowrie from Angus and first landed....For in the place where he landed, he built from the foundations a church to be dedicated to Blessed Peter...From there he set off to preach at the village of Tellein [Tealing], three miles [away]...and founded another church dedicated to the name of the same apostle: (he founded) a third at Restenneth...Having stayed there some years...he penetrated the rest of Angus, Mearns, Mar, Buchan, Strathbogie and Moray, instructing the pagan nations in the doctrine of Christ...' and he died at Rosemarkie in the Black Isle, where his shrine was.

A variant stated that a king of Picts, Nechtan, was baptised and gave the place of his baptistery and the whole region to Kiritinus, and St Kiritinus came 'bearing with him many relics of the apostles and martyrs and other saints, founded a church at the mouth of the River Gobriat in Pictland, and consecrated it. And he evangelised the Picts and Scots for sixty years, and build a splendid church in Rosemarkie.'

It is interesting to note, in passing, that Curetán migrated north within the land of the Picts, just like Drostan of Glen Esk (subject of a previous post). Recent historians have adjusted our perspective on the power centres of the Picts and advised that the most powerful dominion, sometime known at Fortriu, lay in the north. So perhaps these early clerics migrated to reach the epicentre of royal power. A. B. Scott argues (The Pictish Nation, p. 378) that the native Church in southern Pictland was too strong to allow the Romanising incomer Curetán-Boniface to gain a long-term presence in Angus and forced him to journey north.

Yet another version (in the Aberdeen Breviary) has the saint - this time called only Boniface - arriving with his retinue at Restenneth and being met by the king Nechtan and his army there.

This king is thought to be Nechtan son of Derile, 8th century ruler, who was in touch with Northumbria and asked the rulers of that Anglo-Saxon kingdom to send him architects to build a church of stone. The long-held conjecture that this church was indeed the kirk of Restenneth is no longer credited - or rather, the current building at Restenneth cannot represent that church. It is worth noting also that a chapel to St. Boniface once stood on a rising ground about half a mile south of Forfar. Its foundations were visible in 1822, when there were traces of graves in its burying ground.

Whether Curetán was a Roman papal envoy, a religious representative of Northumbria or a native churchman, it is very probably that he came at the head of a group of priests and founded a significant church at Dargie/Invergowrie. Even in the shadow world of early saints in northern Britain this cleric's identify is barely discernible. W. Douglas Simpson would make him a 'romanizing Celt...the clerical instrument of King Nechtan's radical policy'. Why did he specifically and conspicuously choose to arrive at Invergowrie? The supposed early date given by some sources (the 5th century) is a red herring. There may have been an established royal estate in this place, if we judge by (admittedly later) carved stones erected in this locality. Just to the north-west is the Angus parish of Benvie, with its own Pictish stones, surely representing a place of secular power. Bullionfield is, as we see, just north of Invergowrie. The relation of this boulder to even more ancient monuments - un-carved stones - will be considered in the third post. The area was of course already entirely Christian.

The pattern of possibly ancient St Peter dedications in the area make sense within the context of the story of the coming of this saint, whoever he was. Tealing and Restenneth show every sign of being very old Christian settlements. Also important to look at is the site of Meigle to the north - also on the Angus/Gowrie border - and a very important Pictish royal site, which also happens to be dedicated to St Peter.

As for the king involved, Nechton (or Naition) son of Derile, his story may better be placed in a future piece about Restenneth. Suffice it to say that this 'philosopher king' - like the saint - is an enigma, well expressed by Thomas Owen Clancy:

It is worthy of note regarding the northern-centric state of current Pictish studies that the recent full length published study of the king by Julianna Grigg, which examines Curetán in some detail does not even mention Invergowie. Nor does another recent, standard history of early Scotland, From Caledonia to Pictland by James Fraser (2009), mention the saint's southern Pictish associations even in passing.This man - otherwise called Boniface Queritinius - travelled from Italy in the company of wise men and sailed into the Firth of Tay, 'to the mouth of the little river, which now separated the district of Gowrie from Angus and first landed....For in the place where he landed, he built from the foundations a church to be dedicated to Blessed Peter...From there he set off to preach at the village of Tellein [Tealing], three miles [away]...and founded another church dedicated to the name of the same apostle: (he founded) a third at Restenneth...Having stayed there some years...he penetrated the rest of Angus, Mearns, Mar, Buchan, Strathbogie and Moray, instructing the pagan nations in the doctrine of Christ...' and he died at Rosemarkie in the Black Isle, where his shrine was.

A variant stated that a king of Picts, Nechtan, was baptised and gave the place of his baptistery and the whole region to Kiritinus, and St Kiritinus came 'bearing with him many relics of the apostles and martyrs and other saints, founded a church at the mouth of the River Gobriat in Pictland, and consecrated it. And he evangelised the Picts and Scots for sixty years, and build a splendid church in Rosemarkie.'

It is interesting to note, in passing, that Curetán migrated north within the land of the Picts, just like Drostan of Glen Esk (subject of a previous post). Recent historians have adjusted our perspective on the power centres of the Picts and advised that the most powerful dominion, sometime known at Fortriu, lay in the north. So perhaps these early clerics migrated to reach the epicentre of royal power. A. B. Scott argues (The Pictish Nation, p. 378) that the native Church in southern Pictland was too strong to allow the Romanising incomer Curetán-Boniface to gain a long-term presence in Angus and forced him to journey north.

Yet another version (in the Aberdeen Breviary) has the saint - this time called only Boniface - arriving with his retinue at Restenneth and being met by the king Nechtan and his army there.

This king is thought to be Nechtan son of Derile, 8th century ruler, who was in touch with Northumbria and asked the rulers of that Anglo-Saxon kingdom to send him architects to build a church of stone. The long-held conjecture that this church was indeed the kirk of Restenneth is no longer credited - or rather, the current building at Restenneth cannot represent that church. It is worth noting also that a chapel to St. Boniface once stood on a rising ground about half a mile south of Forfar. Its foundations were visible in 1822, when there were traces of graves in its burying ground.

The Followers of Curetán-Boniface

The Aberdeen Breviary names the ecclesiastical landing parting accompanying Curetán at Invergowrie as 'the most devout men bishops Bonifandus, Benedictus, Servandus, Pensandus, Madianus, and Precipuus'. Bringing up the rear were 'two shining virgins, the abbesses Crescentia and Triduana'. Also in the throng were seven priests, seven deacons, seven subdeacons, seven acolytes, seven exorcists, seven readers, plus seven door-keepers and a great multitude of others. Some local names and dedications in the Carse of Gowrie were once thought to some of these followers. But not all of the names may commemorate these saints. According to James Murray Mackinlay (Ancient Church Dedications in Scotland, 1914, p. 481):

Among those who, according to his legend, accompanied St. Boniface were St. Pensandus and St. Madianus. The former is still remembered in the name of Kilspindie in the Carse of Gowrie; and the latter, according to Bishop Forbes, in that of St. Madoes higher up the Carse. With more probability, however, St. Madoes may be attributed not to St. Madianus but to St. Modoc.

And, according to the Rev Philip:

Two of the bishops who are said to have accompanied him were Pensandus and Madianus, whose names are perhaps preserved in Kilspindie and St. Madoes in the Carse of Gowrie. But Johnston derives Kilspindie or Kynspinedy from Gaelic, ceann spuinneadaire, 'height of the plunderer.'

Arthur Dalgetty, in his local study of Liff, summarises some of the speculation derived from Scott's The Pictish Nation. Kingoodie, the riverside hamlet just west of Invergowrie, takes its name (according to Scott) from a corruption of Kin-Curdy - the kin element being swapped for kil, 'church', representing an ancient 'church of Curetán'. Dalgetting adds, 'This would imply that for a time there were two churches at Invergowrie, one at Dargie which adhered to the older Celtic usage, the other at Kingoody following the Roman usage' (The Church and Parish of Liff, p. 36). But this speculation is far from convincing. Although there has never been any evidence of an actual church at Kingoodie a group of long-cist burials, possibly dating from between the 6th and 8th century, has been found just north of the headland.

The Rev. Philip also admits some uncertainty about the name:

The Rev. Philip also admits some uncertainty about the name:

The meaning of Kingoodie, anciently written Chingothe, Kyngudy, Ceinguddie, Kingudie, Kingaidy, is puzzling...Goodie may be the Gaelic Gaoth, gen Gaoithe, the wind. Ceanngaoithe, or with the article Ceannagaoithe, the headland of the wind. (The Parish of Longforgan, p. 310.)

Conclusions

The pattern of possibly ancient St Peter dedications in the area make sense within the context of the story of the coming of this saint, whoever he was. Tealing and Restenneth show every sign of being very old Christian settlements. Also important to look at is the site of Meigle to the north - also on the Angus/Gowrie border - and a very important Pictish royal site, which also happens to be dedicated to St Peter.

As for the king involved, Nechton (or Naition) son of Derile, his story may better be placed in a future piece about Restenneth. Suffice it to say that this 'philosopher king' - like the saint - is an enigma, well expressed by Thomas Owen Clancy:

Was Naiton an English imperialist flunky? A Romanist stooge, allowing the authority of

the Pope and St Peter into his realm? Or, conversely, a Pictish nationalist, rejecting the insidious Irish influences of the Celtic church?

The Ancient Carved Stones

The authors Allen and Anderson note that two cross slabs were built into the empty windows of the ruined kirk. These were put into their Class III monuments, meaning they were later than earlier carved stones, possibly from the 10th century. The stones were donated to the National Museum of Scotland in 1947. Headstones were places into the window vacancies after the slabs were removed.

Andrew Jervise stated in 1855 that the early stones were found in the basement of the church, but giver no further details.

Andrew Jervise stated in 1855 that the early stones were found in the basement of the church, but giver no further details.

|

| Front and rear of slabs formerly built into the windows of the Dargie Kirk from Allen and Anderson's book |

The stones are described by Warden in Angus or Forfarshire, volume 1 p. 27:

The cross is adorned with interlaced tracery of different patterns, with other ornaments. On the reverse are the figures of three men curiously attired, two of which have shoulder brooches, and are evidently ecclesiastics, with scroll work underneath... A fragment of another stone is built into the wall of this church. A portion of a cross is shown, exhibiting the top of the cross and arms, with the circle around same. On the opposite side is a portion of a horse and a figure upon it, above which are the lower parts of the bodies of two or three human beings.

The Bullion Stone

The stone known as the Bullion Stone found just north of Invergowrie in 1934 is a unique artefact (now in the National Museums of Scotland). I wrote about in previously in a previous post very briefly and none too seriously (it can be found here: A Word About the Wee Man). But it deserves more consideration. This sculpture shows a human figure on horseback, but not a young warrior in his prime. Rather he is bearded and balding and none too slender. His mount, going uphill, seems to struggle with its burden. The rider holds aloft a drinking horn whose terminal - a bird's head - stares back at him quizzically. The carving is unique. It has been considered as possibly part of a frieze and this brings to mind the arched stone from the Pictish power centre at Forteviot in Perthshire (also now in Edinburgh) and makes me wonder whether the Bullion Stone, like this one, came from the entrance display of a high status hall or residence here. If so, it has not been discovered by archaeology and may well have been obliterated by widening of the main Dundee-Perth road. But it adds another dimension to the Pictish landscape locally. The visual artist David Watson Hood has a very interesting article about the stone on his website (www.twocrows.co.uk).A Legend of Invergowrie Burn

To finish with - as a kind of mental palette cleanser - is a poem by Alexander Hutcheson, who did so much to describe the ancient monuments of Invergowrie and area. It has little to do with any of the above, apart from a shared location. He wrote the verse in his boyhood, and it remembers a real incident when coffin bearers crossed the Invergowrie Burn and lost the body they were carrying in that stream. The slap which was used as a bridge across that water may well have been another, re-used ancient monument.

'Twas springtime, the bleakness of winter was gone,

The sun on the glad earth brightly shon:

And the rains of night hung in pearly sheen

Upon every leaf with a freshening green.

But alas! The sun and the fostering breeze

That awoke to beauty and life the trees,

That breathed in the air from the earth and the sea,

Like the notes of some witching melodie,

Could not breathe on the human clay, - cold as a stone.

Nor open the eyes from which life had gone:-

In a thatch-covered cottage was weeping and wailing,

Say, what was the cause such a sorrow entailing?

'twas the father, - the husband, - the head, - the provider!

The widow must weep, and her children beside her.

The neighbours were gathered, o'er the coffin they bended,

'Twas lifted, - the procession then mournfully wended,

Solemn and slow were their sad steps who bore him,

That dark home behind and that wide grave before them,

Till they came to the long stone, the burn that crosses,

All covered with lichens and velvety mosses;

The burn was swollen with the rains of the night

And the foam on its waters was flashing and white:

With the speed on an arrow it hurried below

The long narrow bridge where the mourners must go:

Did one of the mourners tremble with fear

As the roar of the waters grew loud in his ear?

Why trembled his hold so, - why shook every limb?

Why wavered his footsteps, why grew his eyes dim?

The nerveless hand slipped, away went the spoke,

The corse from the grasp of the mourners broke,

One splash in the current, one cry of dismay,

And the coffin was hurrying out to the Tay.

The mourners rushed, - they might rush on forever,

For swifter than they rushed the stream to the river,-

Rushed on to the ocean, the food of the grave

Was soon a black speck on the breast of a wave.

Selected Sources

Allen, J. R., and Anderson, J., The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, 2, volumes (Edinburgh, 1903).

Dalgetty, A. B., The Church and Parish of Liff (Dundee,1940).

Grigg, J., The Philosopher King and the Pictish Nation (Dublin, 2015).

Hutcheson, Alexander, Old Stories in Stones and Other Papers (Dundee, 1927).

Jervise, A., 'Notices descriptive of the localities of certain Sculptured Stone Monuments in Forfarshire, viz., - Benvie, and Invergowrie; Strathmartin, and Balutheran; Monifieth; Cross of Camus, and Arbirlot,' Part III. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 2 (3). Vol 2(3) (1855), pp. 442-450.

MacDonald, A., Curadán, Boniface and the Early Church of Rosemarkie (Rosemarkie, 1992).

Macdonald, A. D. S. and Laing, L. R., 'Early Ecclesiastical Sites in Scotland: a Field

Survey, Part II,' Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 102 (1970), pp. 129-45.

MacGibbon and Ross, D and T., The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Scotland From the Earliest Christian Times to the Seventeenth Century, volume 3 (Edinburgh,1896-7).

Macquarrie, A., (ed.), Legends of the Scottish Saints, Readings, Hymns and Prayers for the Commemoration of Scottish Saints in the Aberdeen Breviary (Dublin, 2015).

Philip, Rev. A., The Parish of Longforgan (Edinburgh, 1895).

Scott, The Pictish Nation, its People and its Church (Edinburgh and London, 1918).

Simpson, W. Douglas, 'The Early Romanesque Tower at Restenneth Priory, Angus,' The Antiquaries Journal, 42 (02) (1963), pp. 269-83.

Stuart, J., Sculptured Stones of Scotland, vol. 1 (Aberdeen, 1856).

Taylor, D. B., 'Long Cist Burials at Kingoodie, Longforgan, Perthshire,' Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 93 (1959-60), pp. 202-16.

Warden, Alexander, Angus or Forfarshire, 4 volumes (Dundee, 1880-1885).

Played there as a bairn.

ReplyDeleteSo did I, swinging over the burn from a rope tied to a tree.

DeleteSwing cross the burn and back between Angus and Perthshire.

DeleteWhat a wonderful piece of historical research.

ReplyDelete